Make Laajasalo Productive Again

Helsinki (FI) - Mention Spéciale

DONNÉES DE L’ÉQUIPE

Représentante d'équipe: Laura Martínez (ES) – architecte

Associés: Paula Fernández (ES) – architecte; Wojciech Kębłowski (PL) – géographe; Aníbal Hernández (ES) – anthropologue

ci.ta.europan@gmail.com – ciudadtaller.weebly.com

Voir la liste complète des portraits ici

Voir la page du site en anglais ici

A.Hernández, W. Kębłowski, P. Fernández & L. Martínez

INTERVIEW en anglais

Cliquer sur les images pour les agrandir

1. How did you form the team for the competition?

Ciudad Taller is a collective of urban research, design and activism. Our name stands for “city workshop”: we imagine the city as an open and flexible space in which inhabitants can experiment with different forms and relations of production, property, and exchange. We believe that the urban is where tools and seeds for profound social, economic and political transformations—away from current capitalist mode of production—should be imagined and developed. We perceive the city as a space in which diverse actors constantly negotiate their different interests and aspirations. Uneven social forces, power relations and socio-spatial inequalities can lead to conflict and opposition, or inspire co-operation and partnership; in this essentially political process, we recognise the value of locally-produced knowledge and resources, and the importance of citizen participation and empowerment.

In European 14 we all saw an exciting opportunity to develop and challenge this vision, that brings together our diverse team. Members of the team, besides contributing to Ciudad Taller, have independant careers in architecture, urbanism, geography and anthropology.

2. How do you define the main issue of your project, and how did you answer on this session main topic: the place of productive activities within the city?

The main issue of our project directly relates to the main theme of Europan 14: urban productivity. While it is normally associated with material production oriented towards economic exchange, the term “production” can also relate to many social and cultural activities that focus on use value. Society, economy, politics, culture and nature are entangled and related in complex and fuzzy ways; production in this sense occurs in all spheres.

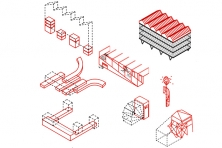

The challenge was therefore to incorporate this definition in an urban environment. We wanted to better understand what kind of “productive” model of urbanism may be encouraged, how it may be implemented, and who should the key agents involved in its development. As a result, and after an analysis of the site, we proposed a set of “productive plug-ins” that could grow, develop or degrow following iterative and collective processes of design and implementation. Rather than propose a closed and complete strategy for productive urbanism, our project delineates a series of principles that we believe are central to making any neighbourhood productive: embeddedness, progressivity and self-management.

3. How did this issue and the questions raised by the site mutation meet?

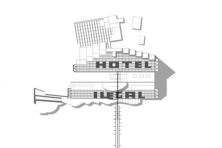

Laajasalo is already a productive ecosystem, with an inspiring territory and a powerful relationship between its urban inhabitants and its natural resources. Here, embeddedness, progressivity and self-management meant also protecting the existing productive configurations: the trees, the sea shore with its small scale marinas and beach, Vaartiosari island, the orography of the terrain, or the walls of rock that are visible from the road, the existing architectures. Together with the site plot all these elements conformed already a specific space where some sites were selected for the location of plug-ins. In this way, the plug-ins, our production nodes, improved the productivity of the boulevard and took advantage of their particular positions.

4. Have you treated this issue previously? What were the reference projects that inspired yours?

We have worked in the question of urban productivity before, production has always been part of our conception of urban space. In this project, we have been particularly inspired by Gibson-Graham’s efforts towards expanding the definition of productive economy, in which they incorporate a variety of apparently mundane and obvious activities such as care and volunteering. We are also deeply inspired by Lucien Kroll, one of pioneers of participation in architecture and planning, who has organised processes to co-design and co-build massive urban developments like La Memé since the 1970´s. Finally, we would like to mention n’UNDO’s work on incorporating the principles of de-growth in architectural practice.

The transformation of space is always a negotiated process between actors with different goals and interests. However, this face of architecture and planning is not often as transparent and inclusive as it should. Our proposal makes an emphasis on this process and on the formal consequences of opening it up to stakeholders that normally have less control over it. We believe that an urban project should develop for and with the inhabitants. Architecture and planning should help to empower them to co-manage their neighbourhood through a variety of participative tools and methods such as citizen panels, participatory budgeting, assemblies and workshops. For us, this is a precondition for urban productivity.

6. Is it the first time you have been awarded a prize at Europan? How could this help you in your professional career?

It is the second time we have participated in Europan. Two years ago our project entitled “Open Space Fabric” was runner-up in Europan 13 in Geneva (CH).